Crafting a mastery-based curriculum to equip our workforce with the skills, knowledge, and leadership abilities needed in today’s complex world requires a good understanding and appreciation of skill acquisition and human competence levels. So let’s start by looking at some common models.

A quick overview of Skill Acquisition Models

Here are the five stages of the Dreyfus model:

- Novice: At this stage, individuals are beginners with no experience in the skills they are learning. They rely heavily on rules and instructions to perform tasks. Their understanding is limited, and they tend to see tasks in isolation without recognizing the bigger picture.

- Competence: At this stage, individuals have gained some experience and can handle more complex tasks. They start to see their actions in relation to goals. They begin to recognize patterns and can prioritize tasks based on their importance.

- Proficiency: At this stage, individuals have gained a good amount of experience and can make decisions based on that experience. They can recognize patterns and nuances that novices and competent individuals might miss. They start to rely less on rules and more on their intuition and analytical abilities.

- Expertise: At this stage, individuals have a deep understanding and can intuitively understand what needs to be done in complex situations. They no longer rely on rules, guidelines, or maxims to connect their understanding of the situation to appropriate action. They have a fluid performance and can innovate as needed.

- Mastery: At this stage, individuals have reached the pinnacle of their skill development. They have a deep and intuitive understanding of the skill and can adapt their performance to fit the situation. They can see the bigger picture and can make decisions that others may find unconventional but are effective.

The Dreyfus model is often used in the field of education, particularly in nursing and software engineering, to describe the process of learning and the stages of skill acquisition. It emphasizes that skills are absorbed over time and through a process of experiential learning rather than through the rote application of rules.

Author

Dehumo Bickersteth

Managing Partner momenta Group

For custom tailored leadership training

Synopsis of Hoffman’s Approach

Hoffman’s approach to skill acquisition is based on the idea of “cognitive flexibility.” Cognitive flexibility refers to the ability to adapt cognitive processing strategies to face new and unexpected conditions in the environment. It is the ability to switch between thinking about two different concepts and thinking about multiple concepts simultaneously.

Hoffman’s cognitive flexibility theory (CFT) was developed to overcome the limitations of traditional instructional methods, particularly in the context of complex and ill-structured domains. It emphasizes the importance of learning in various contexts and the ability to apply knowledge flexibly across different situations.

Here are the key components of Hoffman’s approach:

- Learning in multiple contexts: Hoffman’s approach emphasizes learning in various contexts. This helps learners understand the many ways that a concept or skill can be applied, which in turn promotes cognitive flexibility.

- Case-based instruction: Hoffman’s approach often uses case-based instruction, where learners study multiple examples or cases. This helps learners see how the same basic principles can be applied in different situations.

- Knowledge construction, not transmission: Hoffman’s approach emphasizes that learners should construct their own knowledge rather than simply receiving information from an instructor. This active process of knowledge construction helps learners understand and remember the material more effectively.

- Support for complex learning tasks: Hoffman’s approach provides support for complex learning tasks, such as problem-solving or critical thinking. This support can take many forms, such as guidance from an instructor or using cognitive tools.

- Encouraging reflection: Hoffman’s approach encourages learners to reflect on their learning. This reflection helps learners understand their own thought processes, which can improve their problem-solving skills and promote deeper understanding.

In summary, Hoffman’s approach to skill acquisition emphasizes cognitive flexibility, learning in multiple contexts, active knowledge construction, support for complex learning tasks, and reflection. This approach is designed to help learners acquire complex skills and apply them flexibly across various situations.

Examination of Levels of Competence Model

The levels of human competence is a model that describes the stages of learning and the progression of skill acquisition. Noel Burch developed it in the 1970s while he was working for Gordon Training International, and it is often attributed to Abraham Maslow, although it doesn’t appear in his major works. The model is also commonly known as the “Four Stages of Learning” or the “Conscious Competence Learning Model.”

Here are the four stages of the model:

- Unconscious Incompetence: At this stage, individuals are unaware of their lack of skill or knowledge. They don’t know what they don’t know. Mistakes and poor performance often characterize this stage, but the individual is oblivious to these shortcomings.

- Conscious Incompetence: At this stage, individuals become aware of their lack of skill or knowledge. They realize that they don’t know something and can understand the value of the new skill. The process of learning can begin once the individual recognizes their incompetence.

- Conscious Competence: At this stage, individuals know how to do the skill or task, but they need to concentrate and think in order to perform it. The skill is not yet second nature, and it may require a lot of focus and effort to execute.

- Unconscious Competence: At this stage, the individual has practiced the skill so much that it has become “second nature” and can be performed easily without much conscious thought. They can do the task automatically, and it is easy to perform the skill while doing another task.

The model suggests that as we learn, we move from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence, then to conscious competence, and finally to unconscious competence. It’s a useful framework for understanding the process of learning and skill acquisition, and it can be applied to virtually any skill, from driving a car to playing an instrument to mastering a new software program.

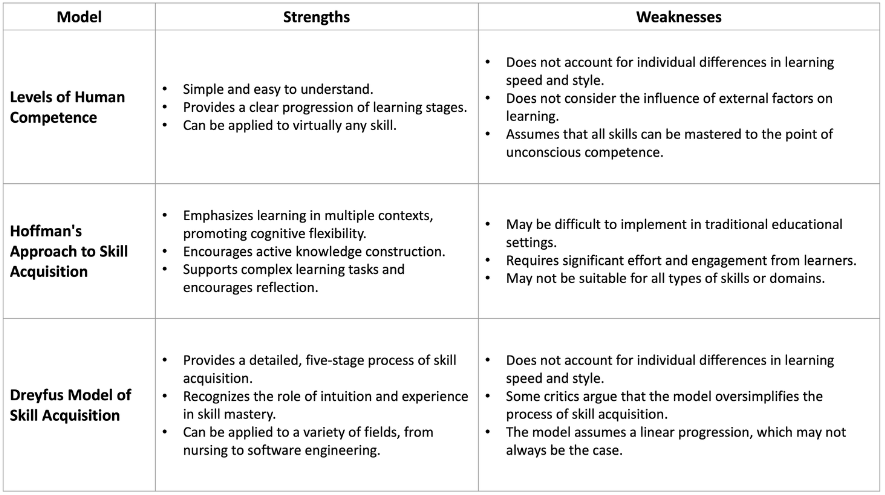

Comparative Analysis: Strengths and Weaknesses of Each Mode

Utilizing Skill Acquisition Models in Curriculum Design

While traditionally, mastery-based curriculum design seeks to ensure that learners can demonstrate mastery over a certain skill or concept before moving on to the next, the essence in the workplace is the recognition of the conscious and deliberate progression from novice to master over time. In order to achieve this, we can incorporate insights from the Dreyfus model, Hoffman’s approach, and the levels of competence to guide and enhance curriculum development.

- Drawing from the Dreyfus Model: The Dreyfus model’s simplicity and universal application make it a valuable tool for curriculum design. Its stages of progression from novice to expert can be used to scaffold learning experiences, ensuring that learners are gradually introduced to more complex tasks and concepts. This provides a roadmap for learners, helping them see where they are in their journey and what they need to do to progress. However, designers should also account for individual differences in learning pace and style and provide ample opportunities for hands-on experience, as per the model’s emphasis on experiential learning.

- Incorporating Hoffman’s Approach: Hoffman’s focus on the cognitive mechanisms of expert performance can be applied in curriculum design to develop higher-order cognitive skills. For instance, tasks and activities can be designed to foster sensemaking, planning, decision-making, and adaptation to novel situations. Moreover, the learning materials can be structured to encourage learners to develop deep conceptual knowledge and rich mental models, enabling them to understand complex situations quickly.

- Applying Levels of Human Competence: the levels of competence model provides a clear framework for understanding the progression of skill acquisition from unconscious incompetence to unconscious competence. This model can be used to structure workplace learning programs, ensuring that employees are provided with the right level of challenge and support at each stage of their learning journey. At the early stages, learning activities might focus on raising awareness of one’s own incompetence and providing clear instructions for skill development. As learners progress, the focus can shift towards developing fluency and automaticity, allowing them to perform tasks efficiently and effectively without conscious thought. However, it’s important to note that not all skills may reach the level of unconscious competence and that conscious competence is often a more realistic goal for many complex workplace skills.

A curriculum designed with these models in mind will guide learners through a progression from novice to expert while fostering the development of complex cognitive skills and refined mental models. This can result in a mastery-based curriculum that not only imparts knowledge and skills but also prepares learners for the complexities of real-world tasks and challenges.

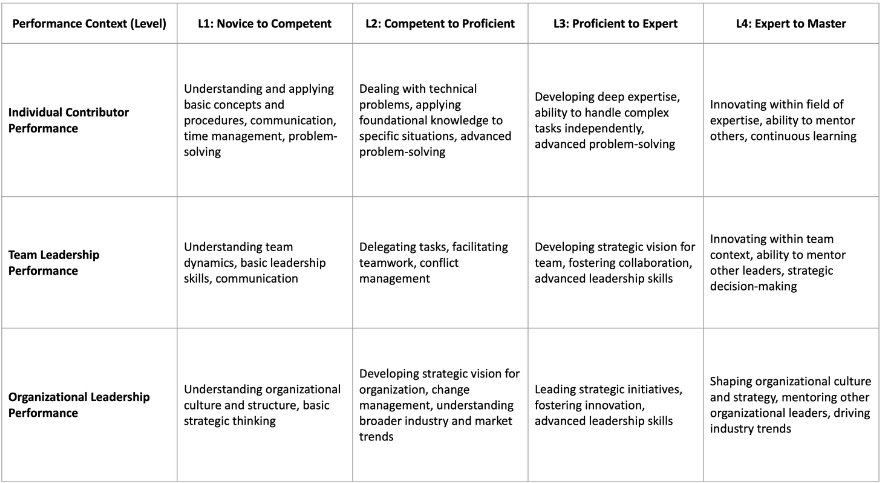

Implementing a Four-Staged, Three-Level Curriculum

In the rapidly evolving world of work, the need for continuous learning and skill development has never been greater. To meet this need, I propose a transformative approach to workplace learning: a four-staged, three-level curriculum designed to guide learners from novice to master while fostering the development of complex cognitive skills and refined mental models.

This innovative curriculum structure is grounded in established theories of skill acquisition and human competence, offering a robust framework for learning and development. It strikes a delicate balance between prescribed and discretionary learning elements, optimizing empowerment and engagement while ensuring that learners acquire the necessary skills and knowledge.

The curriculum is divided into four stages, each representing a different level of competence: from novice to competent, competent to proficient, proficient to expert, and finally, expert to master. At each stage, the balance of prescribed learning shifts, gradually giving way to more discretionary, self-directed learning as learners gain competence and confidence.

In addition to these four stages, the curriculum also encompasses three levels of performance context: individual contributor performance, team leadership performance, and organizational leadership performance. This multi-level approach ensures that employees are not only developing as individual contributors but also as they take on non-individual contribution roles as team leaders and organizational leaders.

Underpinning this curriculum are core learning principles such as deliberate practice, reflective practice, and augmenting and scaffolding. These principles guide the design of learning activities, ensuring that learners are actively engaged in their learning journey and are given the support they need to progress.

Finally, the curriculum leverages a variety of touchpoints, including subject matter experts, specific skill experts, practitioner experts, digital platforms, workshops, and real-world workplace experiences. These diverse touch-points cater to different learning styles and provide various learning experiences, enhancing the overall effectiveness of the curriculum.

This four-staged, three-level curriculum offers a comprehensive and flexible approach to workplace learning designed to foster skill mastery and prepare learners for the complexities of real-world tasks and challenges. It’s not just about imparting knowledge and skills but about empowering learners to take ownership of their learning journey and equipping them with the tools they need to thrive in the modern workplace.

The Four-Staged Journey to Mastery

L1: Novice to Competent

At this initial stage, the curriculum is heavily prescribed, with something like 80% of the learning being guided. This stage lays the foundation of knowledge and skills, providing learners with the basic tools they need to progress. The focus is on understanding and applying basic concepts and procedures. Learners are introduced to the fundamental aspects of their roles and the specific skills they need to perform their tasks. The goal at this stage is to move learners from a state of unconscious incompetence, where they are unaware of their lack of skill, to conscious incompetence, where they recognize their areas for improvement. This stage aligns with the ‘novice’ stage of the Dreyfus model, where learners rely heavily on rules and instructions.

L2: Competent to Proficient

At this level, more discretion is given, with about 60% of the learning prescribed. This stage introduces the relationship between deeper knowledge and the contextual efficacy of decisions and actions. Learners start dealing with technical problems, applying their foundational knowledge to specific situations. The goal at this stage is to move learners from conscious incompetence to conscious competence, where they can perform tasks correctly with effort and concentration. This stage aligns with the ‘competence’ and ‘proficiency’ stages of the Dreyfus model, where learners start to see their actions in relation to goals and can recognize patterns.

L3: Proficient to Expert

At this stage, the learning support is mostly discretionary, with about 40% or less of the learning being prescribed. This level introduces the need to let go of knowledge and expertise and focus on creative solutions with social and emotional emphasis. Learners focus on dealing with adaptive challenges and wicked problems, requiring them to think critically and adapt their knowledge to new situations. The goal at this stage is to move learners from conscious competence to unconscious competence, where they can perform certain enabling tasks correctly and efficiently without conscious effort, freeing them up to tackle the more complex challenges. This stage aligns with the ‘expertise’ stage of the Dreyfus model, where learners have a deep understanding and can intuitively understand what needs to be done in complex situations.

L4: Expert to Master

At this final stage, very little of the learning is prescribed. The focus is on the foundational principles of self-actualization, maintaining reflexive competency, and adaptive performance capabilities. Learners are encouraged to innovate, question, and push the boundaries of their knowledge and skills. This stage aligns with the ‘mastery’ stage of the Dreyfus model, where learners have reached the pinnacle of their skill development and can adapt their performance to fit the situation.

In each stage of this journey to mastery, the principles of skill acquisition and levels of human competency are applied to guide learners’ progression. The curriculum is designed to provide the right level of challenge and support at each stage, fostering the development of complex cognitive skills and refined mental models as well as optimal, highly efficient, and contextually effective psychomotor skills and sensory capabilities.

Three-Level Performance Context

Performance Context 1: Individual Contributor Performance

At this level, learners apply their skills and knowledge as individual contributors. They focus on mastering their own tasks and responsibilities. Skill acquisition at this stage involves gaining proficiency in specific tasks and roles. Performance is largely measured by the individual’s ability to complete their tasks effectively and efficiently. Competency involves not only technical skills but also soft skills like communication, time management, and problem-solving. As learners progress from novice to master, they develop deep expertise, the ability to handle complex tasks independently, and the capacity to innovate within their field of expertise. They also learn to mentor others and commit to continuous learning.

Performance Context 2: Team Leadership Performance

At this level, learners are no longer just individual contributors. They take on leadership roles within teams, requiring them to apply their skills and knowledge in a way that benefits the entire team. Skill acquisition at this stage involves learning to manage others, delegate tasks, and facilitate teamwork. Performance is measured not only by the individual’s output but also by the performance of the team as a whole. Competency involves leadership skills, emotional intelligence, and the ability to manage conflict and foster collaboration. As learners progress from novice to master, they develop a strategic vision for the team, foster collaboration, and acquire advanced leadership skills. They also learn to innovate within the team context, mentor other leaders, and make strategic decisions.

Performance Context 3: Organizational Leadership Performance

At this level, learners take on leadership roles within the entire organization. They must apply their skills and knowledge strategically, making decisions that affect the entire organization. Skill acquisition at this stage involves strategic thinking, change management, and understanding the broader industry and market trends. Performance is measured by the organization’s success, including factors like profitability, market share, and employee satisfaction. Competency involves strategic vision, change management skills, and the ability to inspire and lead the entire organization. As learners progress from novice to master, they learn to shape the organizational culture and strategy, mentor other organizational leaders, and drive industry trends.

In each of these performance contexts, the principles of skill acquisition and levels of human competence are applied in different ways. The focus shifts from individual tasks to team performance to strategic leadership, requiring learners to adapt and expand their skills and knowledge continually.

Summary Table

Core Learning Principles

The Core Learning Principles, which are the foundation of the proposed curriculum design, are informed by several key theories and research findings in the field of education and cognitive science. Three of these principles are described below.

Deliberate Practice

Deliberate practice is a key principle in skill acquisition and competency development. It involves focused, goal-oriented practice with immediate feedback and opportunities for repetition and refinement. This principle aligns with the progression from ‘conscious incompetence’ to ‘conscious competence’ in levels of human competence model, where learners need to practice their skills consciously and deliberately to improve. In the Dreyfus model, deliberate practice is crucial in the early stages of learning, where learners need to practice following rules and guidelines until they become automatic. In the context of our curriculum, deliberate practice is integrated into each stage and level, with learning activities designed to provide learners with clear goals, immediate feedback, and opportunities for repetition and refinement. This principle is based on the work of Ericsson et al. (1993) who found that the key to achieving expertise in any field is not just a matter of time spent, but the quality of practice. Deliberate practice involves focused, goal-oriented training activities designed to improve specific aspects of performance. It requires immediate feedback, repetition, and gradual increases in complexity. A study by Taras et al. (2023) demonstrated the effectiveness of Rapid Cycle Deliberate Practice (RCDP) in medical education, where learners achieved mastery of skills through repetition, feedback, and increasing difficulty.

Reflective Practice

Reflective practice involves thinking about one’s own learning and performance, identifying areas for improvement, and making adjustments as necessary. This principle is key to developing ‘conscious competence’ in levels of human competence model, where learners need to reflect on their performance to identify their areas of incompetence and work on them. In the Dreyfus model, reflective practice is particularly important in the ‘proficient’ and ‘expert’ stages, where learners need to reflect on their performance to make intuitive judgments and decisions. In our curriculum, reflective practice is encouraged at all stages and levels, with learners encouraged to reflect on their learning and performance, identify areas for improvement, and make adjustments as necessary. Reflective practice, as proposed by Schön (1983), involves thinking critically about one’s actions during and after the event to gain insights and improve future performance. This principle is crucial in helping learners understand their thought processes, identify areas of improvement, and apply learned concepts in different contexts.

Augmenting and Scaffolding

Augmenting and scaffolding involve providing learners with the right level of support and challenge at each stage of their learning journey. This principle aligns with the progression through the stages in both the Dreyfus model and levels of human competence model, where learners need more guidance and support in the early stages and more autonomy and challenge in the later stages. In the proposed curriculum, augmenting and scaffolding are integrated into each stage and level, with learning activities and support mechanisms designed to provide the right level of challenge and support for each learner.

- Augmenting: This principle is based on the idea of augmenting or enhancing the learning process with additional resources or tools. This could involve the use of technology, visual aids, or other resources that support and enhance understanding and retention of information.

- Scaffolding: This principle is rooted in Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of learning and the idea of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which involves providing support to learners as they develop new skills or knowledge. Over time, this support is gradually removed as learners become more competent, allowing them to become independent problem solvers.

These principles are not standalone. They interact and reinforce each other to create a rich, supportive, and effective learning environment. For instance, deliberate practice often involves scaffolding, where learners are initially provided with support and feedback, which is gradually reduced as they gain competence. Similarly, reflective practice can enhance deliberate practice by helping learners identify specific areas they need to focus on during their practice sessions. Augmenting can support all these processes by providing resources and tools that enhance understanding and facilitate both practice and reflection.

These core learning principles guide the design of the curriculum, ensuring that learners are actively engaged in their learning journey and are given the support they need to progress. They also align with the principles of skill acquisition and levels of human competence, providing a robust framework for learning and development.

Curriculum Touch-Points

People

People are a crucial touch-point in the learning journey. They can provide guidance, feedback, and support, and they can also serve as role models, demonstrating the skills and behaviors that learners are striving to develop.

- Subject Matter Experts: These individuals have deep knowledge and expertise in a particular area. They can provide detailed explanations and insights, helping learners understand complex concepts and procedures. This aligns with the early stages of the Dreyfus model and levels of competence model, where learners need clear instructions and explanations. Subject matter experts can also help learners develop accurate and comprehensive mental models in their area of expertise.

- Specific Skill Experts: These individuals have mastered a specific skill. They can demonstrate the skill, provide tips and techniques, and give feedback on learners’ performance. This aligns with the ‘conscious competence’ stage in levels of competence model, where learners need to practice a skill deliberately and get feedback to improve. These experts can help learners refine their mental models of how to perform the skill effectively.

- Practitioner Experts: These individuals have extensive experience applying their skills and knowledge in real-world contexts. They can share their experiences, discuss case studies, and help learners understand the nuances and complexities of real-world practice. This aligns with the ‘proficient’ and ‘expert’ stages in the Dreyfus model, where learners need to develop a deep, intuitive understanding of real-world contexts. These experts can help learners develop and refine their mental models based on real-world experiences and challenges.

Channel Touch-Points

Channel touch-points refer to the different modes or platforms through which learning can occur. Each channel has its strengths and can support different aspects of the learning journey.

- Digital: Digital channels, such as online courses, apps, and virtual simulations, can provide flexible, personalized learning experiences. They can support deliberate practice by providing interactive exercises and instant feedback. They can also support reflective practice by allowing learners to review their performance data and track their progress over time. Advanced technologies like AI can personalize learning experiences based on each learner’s progress and needs, while digital twins can provide realistic, immersive simulations for practice. These technologies can help learners develop and refine their mental models by providing rich, interactive, and personalized learning experiences.

- Workshops: Workshops provide opportunities for hands-on practice, group work, and face-to-face interaction with instructors and peers. They can support the development of ‘conscious competence’ in the levels of competence model, where learners need to practice their skills and get feedback. They can also support the ‘proficient’ and ‘expert’ stages in the Dreyfus model, where learners need to develop their intuitive judgment and decision-making skills. Workshops can also help learners refine their mental models through discussion, reflection, and feedback.

- Real-World/Workplace: Real-world or workplace learning involves applying skills and knowledge in real-world contexts. This can support the ‘proficient’ and ‘expert’ stages in the Dreyfus model, where learners need to develop a deep, intuitive understanding of real-world contexts. It can also support the development of ‘unconscious competence’ in the levels of competence model, where learners need to apply their skills automatically and efficiently in different situations. Real-world experiences can help learners refine their mental models based on actual challenges and feedback.

These touchpoints are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary. A well-designed curriculum will leverage all these touch-points, providing a rich, varied, and supportive learning environment that caters to different learning needs and preferences. It will also align these touchpoints with the stages of skill acquisition and levels of human competence, ensuring that learners get the right support and challenges at each stage of their learning journey.

In Summary…

Designing a mastery-based curriculum for workforce development is a complex but rewarding process that requires a deep understanding of the principles of skill acquisition and levels of human competence. By integrating these principles with a four-staged, three-level curriculum, we can create a learning journey that guides employees from novice to master, from individual contributor to organizational leader.

The core learning principles of deliberate practice, reflective practice, augmenting, and scaffolding provide a robust framework for learning and development. By leveraging various touch-points, including people and channels, we can provide a rich, varied, and supportive learning environment that caters to different learning needs and preferences.

However, the journey doesn’t end here. As educators and curriculum designers, we must continually adapt and refine our approach based on new research findings, technological advancements, and feedback from employees. We must also remember that each employee is unique, with their own strengths, weaknesses, and learning styles. Therefore, we must strive to provide personalized learning experiences that cater to each employee’s needs and help them reach their full potential.

So, let’s take the first step on this journey together. Let’s embrace the principles of skill acquisition and levels of human competence, and let’s design a mastery-based curriculum that truly prepares our workforce for the complexities of the real world. Let’s not just train our employees but empower them to become lifelong learners and leaders in their fields.